|

When I mention the ‘P’ word to a group of tweens, it usually incites squeals of embarrassment and excitement. Girls crave information about what will happen to their body over the next few years but are often not quite sure how, who or where to ask.

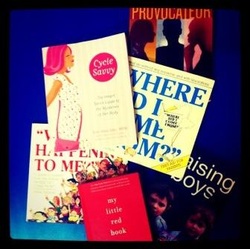

It can be a difficult time for parents. They may feel excitement at their girl reaching the next stage in life. But there is sometimes also a sense of sadness that their little girl is growing up or anxiety about how their girl will cope, particularly if she is young. Many parents are embarrassed or reluctant to discuss puberty with their children and often feel that they don’t know enough to teach them – if you feel this way, you are not alone! The most important thing you can do with the girls in your life is talk, talk, talk! Rather than having a single “puberty talk”, it needs to be an ongoing conversation. Seize upon teachable moments to discuss puberty and related issues with your daughter. The more we talk, the easier it gets, and girls start to see periods as a normal part of the female experience. I’ve found it distressing helping girls who have come to me in absolute shock because their period had started and they didn’t know what to do, because no one had ever talked to them about it. I got my period when I was 11 and I had no idea what was happening. My mother just said it was horrible and dirty and refused to discuss it. My Dad explained in horribly embarrassed terms. It was really traumatic. – Emma My mum and I were sitting in the doctor’s waiting room and there was a poster on the wall with a picture of a toilet and the words ‘If you see blood in here, talk to your doctor.’ Obviously my mother saw it and thought it would be a good time to give me the period talk – without actually using the words period, menstruation, monthly, tampons or pads. She simply said, ‘If you see blood in your undies, let me know.’ For years I thought she was talking about bowel cancer. – Kim Powell If you are a reluctant puberty talker, there are some great resources that can help you become more comfortable, including these books, Menstruation.com.au and Puberty Girl author Shushann Movsessian’s website. Also look for parent workshops in your area. In many cultures, a girl’s first period is a rite of passage that is revered and celebrated. In our culture, particularly among girls who menstruate early, periods are often associated with embarrassment and confusion. We need to reclaim this. Give your daughter the message that her body is beautiful and incredible. For some mothers, this may involve healing of their own, as many women carry with them the shame and confusion they experienced with menstruation as a child. Some families like to celebrate – go out for ice-cream or have a celebration with family. Other girls prefer to keep it private. The most important thing to consider is your daughter’s wishes, as this woman illustrates: I got my first period during a family dinner and Mum announced it to the whole family. My grandfather hugged me – this did not help!!! I cried. Mum made Dad go out and buy a cake – my nana called it a period cake. It was a hideous experience! - Hannah Make sure girls know what tampons and pads are, what they look like and what they are for. There are many opportune teachable moments for this to happen. When I was about 10 there was a tampon ad on TV. My mum launched in to an account of the ‘menstrual cycle’ and told me that one day I too would need to use tampons. She gave a good biological description, but I was a bit confused because I couldn’t work out what the beach and white swimsuits had to do with periods! – Chloe Keep in mind that you may not be there when your daughter’s period starts, and it will be much easier for her if she can deal with it herself. Have supplies ready. If possible, get your daughter her own brand or colour, so she knows they are hers and doesn’t feel she has to sneak things that belong to others in the house. Some parents like to give their girl a ‘pad pack’ that goes discreetly in her school bag in case her period starts at school. I had my first period about 6 months after my mother had died. I was so thankful that she had left me with a box of pads and a puberty book, so that when I got my period I was able to cope by myself. I wasn’t at the stage I wanted to share with my dad – a little too embarrassing – so I managed to cope fine. I think it is important for girls to have a book they can refer to as needed, and a pack of pads and tampons. – Lucinda There are times when your daughter (or son) will have questions that you are unable to answer, or when she would prefer to find out for herself. Books are fantastic for such occasions. Mum brought us home a puberty book to read – we feigned disinterest. I noticed my older brother had been reading it, so I waited for my chance to get it alone (when no one could see me), but before I finished it, Mum returned it to the library because she thought we weren’t interested. ‘But I need to know too!’ I wanted to tell her, but I didn’t. – Laura My parents sat and read ‘What’s Happening To Me?’ with me. I remember being absolutely disgusted at some of the things, and embarrassed reading it with my parents. It was much better when they left me to read it in peace! – Kim Indeed, Peter Mayle’s What’s Happening To Me? is as relevant now as it was when it was first published in 1981. Puberty Girl, an engaging book aimed at preteens, clearly explains the different aspects of puberty. I recommend Cycle Savvy for teen girls (and adult women!) to help them understand the intricacies and wonders of menstruation. My Little Red Book, by Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, is an anthology of short stories from women of all ages from around the world about their first period. It is my favourite book to help girls understand how normal periods are – and how vastly different everyone’s experience of them is. And this is the main message that you need to pass on to your daughter: that pubertal change is not dirty or weird, but simply a normal part of growing up that happens to everyone. Checklist for Parents • Rather than planning a “puberty talk”, make it an ongoing conversation. • Prepare yourself by attending seminars, reading books or searching online. • Ensure your daughter knows ahead of time what menstruation is and how to deal with it. • Find books to help you and your daughter through her puberty journey. • Mothers, share your stories – remind your daughter that you survived puberty once too!

0 Comments

Most women have a very vivid memory of where they were when they got their first period, what they were doing and how they felt. I was 12 and very reluctant to grow up – life was good as a little girl! On the day my period started I was playing make-believe games with my little brother and sister in our garden and I noticed blood on my undies. I cried and cried and cried. I sat by the window for the rest of the day, watching my siblings play, having decided with great sadness that now I had my period I was too old to play those games. I felt a real sense of loss, and also despair that I was no longer in control of my body.

My experience was very different to my colleague Danni Miller's: I didn’t get my first period until I was 15 years old. I was the last within my circle of friends, and by then, even my younger sister was a veteran (oh the indignity). You’ve never seen a teen girl more prepared for this milestone than I was. I had been carrying tampons in my school bag for so long I think they may well have past their use-by date! I had even had practice in breaking the news to parents as my best friend had been too embarrassed to tell her mother when she started her period and I had broken this news for her : “Mrs Manton, our Janelle has become a woman…” The main feeling I recall when I started menstruating was that of relief. Finally, I was in the “big girls” club! I was so elated I ran into my school assembly and screamed out “I have my period!” to my friends- not realising the teachers were already present and waiting to start. My Year Advisor was very gracious and began the assembly by congratulating me. Research indicates that this moment is happening at increasingly younger ages than in previous generations. Over the past 20 years, the average onset of menstruation has dropped from 13 years to 12 years, seven months, and indications are it will continue to drop. As the average age has dropped by five months, it means that those girls at the lower end of the bell curve are also starting earlier. So nowadays it is increasingly common for girls to start menstruating as early as 8 and 9 years old. Researchers have found that 15 percent of American girls now begin puberty by age 7 (measured by the girls’ level of breast development). This is twice the rate seen in a 1997 study, and the findings are likely to be similar in New Zealand and Australia. Why are girls reaching puberty earlier? Some of the more widely supported theories about why this is happening are:

Traditionally, puberty has marked the transition from childhood to adolescence or adulthood. Many girls absorb the message that beginning menstruation means that they are a woman. Just as I did, some girls who get their periods early can experience a sense of grief and loss, as they don’t feel ready to leave childhood. For many girls, puberty marks the moment that they start to define their self-worth by the way they see themselves in the mirror. And all too often the girls don’t like what they see. Such a response is understandable: at the same time as girls are experiencing an increase in body fat and a widening of their hips, they are bombarded with messages from the media that suggest the perfect beautiful body resembles a prepubescent male or has proportions that can only be achieved through disordered eating or extreme Photoshopping. Ella: I was so embarrassed by my body when I was younger that I couldn’t tell my mum I’d started my period, when I was 13. I lost it for 2 years thereafter as my weight plummeted, so I didn’t really have to deal with it and when it came back I was so angry. It meant a) that I had to deal with this THING happening to my body and b) I wasn’t a ‘good enough’ anorexic. My mum tried to talk to me about it, but I’d just slam doors and refuse to talk about it, or hide under my bed. I found the changes in my body very distressing. I remember when I started growing breasts, initially at 12–13 and then again when I’d gained weight at 16–17 and I’d make deals with God that if I didn’t eat/was nice to my brothers/did all my homework/didn’t shout at my parents/etc., etc., that these things would go away. They didn’t. Now I’m kind of glad of that. It is particularly concerning that evidence suggests that girls who reach puberty earlier have a more negative body image than girls who reach puberty when older. Some girls eagerly anticipate their first period because they believe it will propel them into a world of sexual desirability and adult experiences. For girls at both ends of the spectrum, we need to be quite clear that getting your period does not equate to womanhood. Becoming a woman is far more than our bodies changing. We need to be careful about the symbolism we use surrounding menstruation and the expectations we place on girls. Experiencing puberty at a younger age means that girls’ childhoods are being compressed and often their minds are not ready to deal with the changes that their body is going through. Many struggle to understand and cope with hormone-influenced emotions and sexual impulses, and are not ready to deal with sexual interest from males. Physical maturity often doesn’t reflect girls’ cognitive and emotional development. In their study of the evolution of puberty, New Zealand researchers Gluckman and Hanson concluded that for the first time in human history we are maturing physically much earlier than we are maturing psychologically and socially. Meanwhile, our education system and our expectations as parents are grounded in the 19th century, when there was a closer match between physical and psychosocial maturity. “There will have to be adjustment to educational and other societal structures to accommodate this new biological reality,” they write. The effect of this “new biological reality” is compounded by our consumer culture’s relentless march to shorten childhood. Prior to the late 1990s, marketers had not discovered the concept of tween, a phenomenon that now has girls wearing makeup and high-heels and their parents taking them to beauty salons or to get waxed. And the target market gets younger and younger, as we’ve seen with child beauty pageants. Earlier physical maturity, coupled with a highly sexualised society where girls are bombarded with the notion that sexual desirability is of utmost importance is a toxic combination – which is why it’s more important than ever to keep talking with our kids and showing them we love them for who they are, not for what they look like. This is part one of a three-part series. In next week’s post, I will look at what parents can do to best support girls through puberty. I am seeking personal stories about experiences with school sexuality education. Please email me your stories! A couple of months ago Universal Royalty announced that they were heading to Australia. That's right, the company of 'Toddlers and Tiaras' fame decided that Australia needed to glitz up their kids, and they were the people to help! But there was a strong voice of opposition in Australia, and many voiced outrage at the proposal. Catherine Manning founded Pull The Pin and rallies were held all around Australia to draw attention to the pageants and the the harm they cause. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists have backed calls for child beauty pageants to be banned, saying they encourage the sexualisation of children and can cause developmental harm. The chair of the college stated "We're giving these kids messages that how they appear, how they perform and standards about what they're to come up to is actually more important than what they're like inside." Catherine is an Enlighten Education colleague of mine, and last week when Universal Royalty announced they were also New Zealand-bound, Catherine asked me to coordinate the Pull The Pin campaign in New Zealand. I felt honoured to be asked, and set up the Pull The Pin NZ facebook page. We are campaigning to end all child beauty pageants in New Zealand. It is our view that pitting young girls against each other in a competition based on physical beauty is potentially harmful to their development, and can lead to lowered self esteem and other conditions including eating disorders and depression. We are also concerned with the adultification and sometimes sexualisation of pageant entrants, and their engagement in adult cosmetic treatments such as waxing and spray tanning. We are calling on the government to legislate to stop parents and pageant organisers from exploiting children by enforcing age restrictions on beauty pageants and adult cosmetic procedures (unless for medical reasons). We will be co-ordinating public rallies once we have more information on when and where these pageants will be held. It's been fantastic receiving so much support on this issue - it is definitely a topic that many New Zealanders feel strongly about! New Zealand media coverage over the last couple of days:

And if you needed any more convincing that these pageants are NOT something we want to become a part of kiwi culture, check out this video featuring Universal Royalty's Eden Wood: |

AuthorRachel is a writer and educator whose fields of interest include sexuality education, gender, feminism and youth development. Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed