I was privileged to spend some time with some gorgeous girls in Samoa last year. As my blog posting has been sporadic-at-best as of late, this has sat in my 'drafts' way too long! Background In 2013 I was planning a family holiday to Samoa. As someone passionate about social justice, I like to ‘give back’ to the communities I live in and visit. I had helped organised an aid package to go to Samoa Victim Support Group previously, and I thought I may be able to offer a workshop to the girls at their residential shelter. Wellington-based charity SpinningTop connected me to their President Lina and we organised for me to provide a workshop for them. What I Did When we arrived in Apia I met with Lina at the SVSG offices and she gave me more background on their organisation. We discussed what I would be teaching the girls and I gave Lina a couple of boxes of supplies I had brought with me – Air NZ had kindly agreed to transport these for free. The boxes contained some donated stationery items, disposable sanitary pads donated by Kotex, as well as re-usable packs from Days For Girls NZ (containing underwear, cloth pads, and a wash cloth). I spent a morning with approximately 30 girls - the girls were fantastic and really engaged, and the staff were very supportive. The girls were gorgeous, so full of smiles and laughter. They are survivors for whom I have the utmost of respect for. Lina had told me some of their stories, and these girls have all been on traumatic and heartbreaking journeys. Most of them are with SVSG because they are survivors of sexual violence, for many of them this is incest. Many of them have been pregnant as a result of this violence. Tragically in many cases these girls have been disowned and blamed for bringing shame on the family. SVSG provides safety, education and a home for these girls. SVSG also manages the legal process to bring justice for these children. The girls had lots of questions and I felt like we could have spent a lot more time together. The level of knowledge and understanding of how their bodies work was very low. Most knew very little about the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and childbirth - despite there being pregnant girls and girls who had already birthed in the group. My (then 10 month old) daughter Nina accompanied me and I found that having her there was a good ‘icebreaker’ with the girls. The girls enjoyed chatting and playing with Nina as they warmed up to me. As it turned out Nina ended up sleeping in my front-pack for most of the morning as I taught - it was more than 30 degrees in the classroom so we were rather sweaty by the end of it! I was a little taken aback when TV cameras arrived just as we were starting. They filmed the introductory part of my session and then in the middle of the session I was called out for an interview. I was a little anxious about this as had had no warning and I wasn't sure what angle they were going to take, but I kept it very neutral and emphasised the importance of all people having a good understanding of their bodies and sexuality. It came across well on the news that night. I left SVSG feeling like what I had done that day with the girls was but a drop in the ocean. I felt like I had empowered the the girls with knowledge of their bodies, but also knew there was so much information we didn't cover. SVSG were hugely grateful for the workshop, but I wanted to do more. These girls really touched my heart. There is a huge need for ongoing body/sexuality education as well as antenatal education for the pregnant girls. SVSG has been on my mind a lot since. Looking Forward Earlier this year SpinningTop approached me to see if I would be interested in offering a more comprehensive programme for the girls at SVSG. With SpinningTop's support, I am returning to provide a one-week programme in August 2014. I am currently fundraising for supplies (food, baby formula, educational supplies) for SVSG and am hugely appreciative of any donations. For more details on this project, please click here.

4 Comments

This guest post is by Dannielle Miller. Dannielle is a highly respected and experienced educator, author and media commentator on issues affecting teenage girls. She is CEO of Enlighten Education and this post originally appeared on her blog. I had a revealing conversation with a single parent of a 12-year-old girl the other day. His daughter had been feeling particularly moody, he said, as she was just about to menstruate. I asked if she had had this premenstrual phase of her cycle explained to her. “Yes, she knows all about her periods” was his response. Yet I suspected after talking with him further that, as it is for many young girls who are given “the talk”, this conversation was reduced to an explanation of how to care for herself physically during her period. In its most simplistic form, it is often a chat about pads versus tampons, and tends to come with the dire warning that if they are not “careful” they could now fall pregnant. The fact is, once our girls menstruate, we don’t tend to be very helpful in advising them beyond sanitation, abstinence and, if we are particularly switched on, contraception options. Rarely do we discuss how to deal with the fact that for many girls and women emotions may be heightened during the premenstrual phase and behaviour altered. And even if we do allude to premenstrual tension (PMT), it tends to be in terms that promote and reinforce the archetypal “crazy lady” myth, which would have us reduce everything a woman expresses during this time to hysterical ramblings. It is particularly apt that women are often referred to as being “hysterical” during this stage in their cycle, as the term derives from the Greek word meaning “womb” (hence the term “hysterectomy”). Historically, society would have us believe some deep flaw within our wombs is literally making us insane! "One day she is all smiles and gladness. A stranger in the house seeing her will sing her praise . . . But the next day she is dangerous to look at or approach: She is in a wild frenzy . . . savage to all alike, friend or foe . .." Semonides, Greek philosopher (c. 556–468 BC) Premenstrual tension has been recognised as a medical condition since 1953 and has even controversially been used as a defence for murder—hence the headline to this post, which comes from a newspaper report chronicling a 1980s court case in London in which PMT was raised (unsuccessfully, I might add) as a defence for homicide. Premenstrual tension may include physical symptoms such as leg cramps, bloating and headaches; emotional changes such as increased depression and anxiety and lower self-esteem; and behavioural changes including increased irritability, social isolation and being accident prone. I have been known to suffer from particularly bad PMT at various points in my life. Leg cramps? Check. Bloating? Absolutely. Increased depression? I have been known to weep at the thought of making yet another school lunch. Irritability? My ex-husband used to always joke that I would threaten to divorce him once every month. Despite knowing my feelings at this time are certainly heightened, I also believe they are valid. In fact, as I’ve gotten older I’ve learnt to be very attentive to them, as I can often more clearly see, for example, what is wrong in my relationships at this stage. Usually I tend to repress these darker feelings. In a sense, my inner voice stops whispering and starts screaming at me (okay, okay, and often at others) that week! I am no longer so quick to silence my womb and my female intuition. Rachel Hansen, a colleague and sexual health educator, offered me her insights: "In my 20s, I used to dismiss PMT as that time of the month when I was particularly irrational, but I now think of this as a time when I actually allow myself to acknowledge and express the full range of my emotions. Talk about liberating! Menstruation has traditionally been associated with craziness and all things negative. I think that we women have to reclaim this time in our lives, to reclaim it as a particularly special, empowered time – heck, perhaps the closest we get to being Superwoman each month!" A friend who is a mum to two girls explained to me how she supports her eldest daughter to not ignore, but rather manage, her mood swings: "She would get so emotional and fiery, to the point where she was confused and didn’t know what was ‘wrong’ with her and why she kept arguing with us. I sat her down and explained that it’s very normal to feel the way she does and that her feelings are legitimate, but that in the midst of those more out-of-control moments around period time, we need a word to remind her, and us, as to why she’s struggling to articulate herself. I told her to choose a word that reminds her of something calm and happy that she could use, so that she can just say the word, and then that will be our signal to just stop and hug her, to show her that we care about her feelings, but that we need to pick up the conversation later. (Most of the time, what worried her so much is forgotten later anyway.) Her word is ‘unicorns’. This works really well for us and for her, and has made a huge difference." Psychologist Jacqui Manning offered me the following really practical tips for girls (and women) to help them better understand and manage this stage:

Of course, it’s also important to distinguish the feelings that really are worth listening to during this period (pardon the pun) from those that are okay to merely let wash over us. A good friend offered me this when I asked for her thoughts on PMT last week: "Danni, it’s all a bit too close to home for me today given that I’ve spent the morning in bed feeling bloated and crying for no clear reason at all. Based on the thought processes I was having, it has something to do with a letter that was sent about me in high school, a sad movie I once saw, and the fact that my boyfriend doesn’t have time to go out to lunch today. The TRIFECTA!" Certainly our womb-words can seem somewhat confused and irrelevant, but they can also be deeply insightful. I’m choosing to embrace the journey and help my daughters embrace it too. Last week I offered some tips to support parents in talking to their girls about puberty and getting their first period, because now more than ever, parents need to have the knowledge and confidence to be able to discuss sexuality with their children. The work of parents also needs to be backed up by quality holistic sexuality education within all our schools.

If, like many parents, you assume that your child is already getting basic sexuality education at school, think again. Despite the fact that more than half of Australian teenagers are sexually active by the time they are 16, there is no mandatory, comprehensive Australia-wide sex-education policy. In New Zealand, sexuality education is a key area of learning in the National Curriculum, which means that it must be taught at primary- and secondary-school levels. Yet a 2007 report by the New Zealand Education Review Office concluded: “The majority of school sexuality education programmes are not meeting students’ learning needs.” In both countries, there are some schools that offer fantastic programs, but there is no guarantee that your child will be one of the lucky ones. Many parents say to me, “Oh, but my child has no interest/no idea/no awareness about anything to do with sexuality.” This may be true, but their classmates do, and their classmates are talking. If a child isn’t getting information from her family or her school, she will turn to her friends or the internet. I don’t have to persuade you that googling “vagina” is probably not going to throw up much useful advice for a 10-year-old. So I urge schools to do everything they can to meet the physical and emotional needs of students as they reach puberty. Make it age appropriate. As I discussed in an earlier post, puberty is starting earlier for girls, and it is important that they understand what is happening to them before they get their first period. This means that schools need to rethink the age at which they teach students about puberty. In New Zealand for at least the past 40 years, students have been taught about puberty usually in years 7 and 8. As it is not uncommon for girls to start menstruating at age 9 or 10 now, I encourage schools to teach it in years 5 and 6. Don’t segregate! Ensure that the boys in your school are equally well informed about female puberty as the girls, and vice versa. The boys need to be in on the period talks, and the girls need to understand erections and breaking voices. If girls and boys understand what the other is experiencing and why the changes happen, bullying is likely to be greatly reduced. When we had the puberty talk at school, the boys and the girls were separated. I never knew what the boys learnt, but afterwards they were fascinated with our ‘pad packs’ that we’d been given, and they stole them and teased us, demanding to know what we had been told. We were all really embarrassed and didn’t know what to say to the boys. I thought that it would be really naughty if we told them – because obviously our teacher didn’t want them knowing. Because they weren’t taught about it, it made it seem like periods were taboo and secret from boys. — Kelly School was tough. The boys used to grope us to see if we were wearing a pad, then announce to the entire corridor that we had our periods. Or they’d go into your locker looking for pads to steal and stick all over the corridor. — Sophie Stock your library with books and pamphlets on puberty. Age-appropriate books and take-away pamphlets are fantastic for students to access in their own time and when they need answers. Primary schools can be reluctant to put sexuality and puberty books in the library for fear that parents of younger students will complain. One solution that I have seen in some schools is to have a special part of the library dedicated to the older students. These students like it because it’s their special place, and it’s somewhere they can go for answers if they don’t feel comfortable asking their teachers or parents. Make sure students know where to go for help and advice. Students need to know who to go to for support at school if they have concerns or questions about puberty or sexuality. Make sure that girls also know where a supply of pads are kept in case they are caught out. Many schools have these at the administration office, which is always staffed during the day. It is worth having a brief discussion with staff at the start of the year about what to do when a girl gets her period and needs support, as some staff will be unaware of the stress that periods cause some girls. I got my period for the first time in my first week of high school. I was mortified because I didn’t have a pad. My friend went and asked the lady at the front desk and she gave me one – thank goodness! I am not sure what I would have done otherwise. — Laura There was always the fear of getting caught at the far end of school from my locker, needing to change pads and having, in the time a teacher thought was acceptable for a loo stop, to run from one end of the school to another to get supplies. — Sophie Also be sure that girls can dispose of used pads and tampons appropriately. As the average age at which girls get their first period decreases, primary schools now need to make sure there are sanitary bins in the girls’ toilets. I urge parents to encourage their daughter's school to offer quality holistic sexuality education and to check what measures the school is taking to ensure girls are supported through puberty. Most women have a very vivid memory of where they were when they got their first period, what they were doing and how they felt. I was 12 and very reluctant to grow up – life was good as a little girl! On the day my period started I was playing make-believe games with my little brother and sister in our garden and I noticed blood on my undies. I cried and cried and cried. I sat by the window for the rest of the day, watching my siblings play, having decided with great sadness that now I had my period I was too old to play those games. I felt a real sense of loss, and also despair that I was no longer in control of my body.

My experience was very different to my colleague Danni Miller's: I didn’t get my first period until I was 15 years old. I was the last within my circle of friends, and by then, even my younger sister was a veteran (oh the indignity). You’ve never seen a teen girl more prepared for this milestone than I was. I had been carrying tampons in my school bag for so long I think they may well have past their use-by date! I had even had practice in breaking the news to parents as my best friend had been too embarrassed to tell her mother when she started her period and I had broken this news for her : “Mrs Manton, our Janelle has become a woman…” The main feeling I recall when I started menstruating was that of relief. Finally, I was in the “big girls” club! I was so elated I ran into my school assembly and screamed out “I have my period!” to my friends- not realising the teachers were already present and waiting to start. My Year Advisor was very gracious and began the assembly by congratulating me. Research indicates that this moment is happening at increasingly younger ages than in previous generations. Over the past 20 years, the average onset of menstruation has dropped from 13 years to 12 years, seven months, and indications are it will continue to drop. As the average age has dropped by five months, it means that those girls at the lower end of the bell curve are also starting earlier. So nowadays it is increasingly common for girls to start menstruating as early as 8 and 9 years old. Researchers have found that 15 percent of American girls now begin puberty by age 7 (measured by the girls’ level of breast development). This is twice the rate seen in a 1997 study, and the findings are likely to be similar in New Zealand and Australia. Why are girls reaching puberty earlier? Some of the more widely supported theories about why this is happening are:

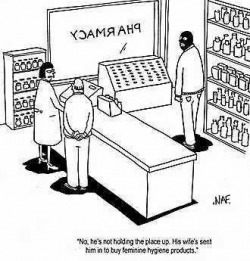

Traditionally, puberty has marked the transition from childhood to adolescence or adulthood. Many girls absorb the message that beginning menstruation means that they are a woman. Just as I did, some girls who get their periods early can experience a sense of grief and loss, as they don’t feel ready to leave childhood. For many girls, puberty marks the moment that they start to define their self-worth by the way they see themselves in the mirror. And all too often the girls don’t like what they see. Such a response is understandable: at the same time as girls are experiencing an increase in body fat and a widening of their hips, they are bombarded with messages from the media that suggest the perfect beautiful body resembles a prepubescent male or has proportions that can only be achieved through disordered eating or extreme Photoshopping. Ella: I was so embarrassed by my body when I was younger that I couldn’t tell my mum I’d started my period, when I was 13. I lost it for 2 years thereafter as my weight plummeted, so I didn’t really have to deal with it and when it came back I was so angry. It meant a) that I had to deal with this THING happening to my body and b) I wasn’t a ‘good enough’ anorexic. My mum tried to talk to me about it, but I’d just slam doors and refuse to talk about it, or hide under my bed. I found the changes in my body very distressing. I remember when I started growing breasts, initially at 12–13 and then again when I’d gained weight at 16–17 and I’d make deals with God that if I didn’t eat/was nice to my brothers/did all my homework/didn’t shout at my parents/etc., etc., that these things would go away. They didn’t. Now I’m kind of glad of that. It is particularly concerning that evidence suggests that girls who reach puberty earlier have a more negative body image than girls who reach puberty when older. Some girls eagerly anticipate their first period because they believe it will propel them into a world of sexual desirability and adult experiences. For girls at both ends of the spectrum, we need to be quite clear that getting your period does not equate to womanhood. Becoming a woman is far more than our bodies changing. We need to be careful about the symbolism we use surrounding menstruation and the expectations we place on girls. Experiencing puberty at a younger age means that girls’ childhoods are being compressed and often their minds are not ready to deal with the changes that their body is going through. Many struggle to understand and cope with hormone-influenced emotions and sexual impulses, and are not ready to deal with sexual interest from males. Physical maturity often doesn’t reflect girls’ cognitive and emotional development. In their study of the evolution of puberty, New Zealand researchers Gluckman and Hanson concluded that for the first time in human history we are maturing physically much earlier than we are maturing psychologically and socially. Meanwhile, our education system and our expectations as parents are grounded in the 19th century, when there was a closer match between physical and psychosocial maturity. “There will have to be adjustment to educational and other societal structures to accommodate this new biological reality,” they write. The effect of this “new biological reality” is compounded by our consumer culture’s relentless march to shorten childhood. Prior to the late 1990s, marketers had not discovered the concept of tween, a phenomenon that now has girls wearing makeup and high-heels and their parents taking them to beauty salons or to get waxed. And the target market gets younger and younger, as we’ve seen with child beauty pageants. Earlier physical maturity, coupled with a highly sexualised society where girls are bombarded with the notion that sexual desirability is of utmost importance is a toxic combination – which is why it’s more important than ever to keep talking with our kids and showing them we love them for who they are, not for what they look like. This is part one of a three-part series. In next week’s post, I will look at what parents can do to best support girls through puberty. I am seeking personal stories about experiences with school sexuality education. Please email me your stories!  I am saddened by the way menstruation is usually referred to in negative ways. Girls usually laugh uncomfotably when I suggest to them that actually their menstrual period is AMAZING and a cause for celebration. And, encouragingly, more often than not they are open to learning to see it in a positive way. In my workshops with adults, women are often keen to share their experiences of their period. I am really interested in DeAnna L'Am's idea of menstruation being a 'chain of pain' that is passed from generation to generation. Today's post is written by DeAnna L’am. DeAnna is a speaker, coach, trainer and author of 'Becoming Peers – Mentoring Girls Into Womanhood'. Her pioneering work has been transforming women’s & girls' lives around the world, for over 20 years. DeAnna specializes in enriching women's lives at any age, helps mothers develop ease & confidence about their girl's puberty, and trains women to hold RED TENTS in their communities. Do you truly believe nature intended women to suffer monthly? This is a rather absurd idea, when you think of it this way, since menstruation is an essential component of women's ability to birth life. Without it, women will not be able to conceive. So how did this happen? How did a natural process become such a problem? Let's look at how menstruation is held by the culture at large. In western cultures women seem to be doomed when they do, and doomed when they don't (bleed, that is). Women are considered to be out of control when they are “on the rag,” and out of control when they are in menopause. Imagine how out of control one might get when their body is tired, their mind fatigued, their emotions exhausted... when every ounce of their being wants to go to sleep, yet they are not allowed to do so.... not only are they denied sleep, they are expected to go to work, be productive, cordial, efficient, and social.... wouldn't you go berserk? Well, women often do, if we buy into the cultural expectation of having “every day of the month be the same”, and push ourselves to prevent menstruation from interfering with our work and life. On top of this, we are also fed a diet of negativity about our menstrual cycle, from a very young age. A cultural taboo, often not mentioned by name, menstruation is referred to as a “necessary evil,” a nuisance, or “the curse”. Now imagine again how you would feel if you were so tired that all you could think of is sleep, yet you were told that your state is “a curse” and you must get over it and get on with your work. Or if you were offered medication to overcome your tiredness, and expected to perform at top notch? Wouldn't you snap? Indeed, this is what happens to many women all over the world, in response to years of internalized negativity about menstruation. This is coupled with the unacknowledged, ignored (and often unconscious) deep yearning to go inward, rest, replenish, and renew, during menstruation. Add cultural hostility to our denied monthly need to regenerate, and what do you get? Out-of-control-raving-mad-lunatic-raging-bitch! And rightly so! Since this is the ONLY way we can express the tension inside us. Or, perhaps, the only culturally acceptable way - to which society reacts by perpetuating the belief in menstrual “badness.” Not being taught to honour our monthly need for regenerating our emotions, and renewing our spirit (while our body renews itself) we not only loath our menstruation, but start developing symptoms, which will make us slow down, stay in bed, rest... This whole chain reaction could have been prevented in the first place, had we slowed down and took time out, monthly, without our body having to scream at us via painful symptoms. This “chain of pain” is passed on collectively by our culture, and individually -- from mother to daughter. Your grandmother was probably handed negative messages from your great-grandmother, your mother from your grandmother, you from your mother, and now, is your daughter receiving this painful legacy from you? How about your granddaughter, stepdaughter, niece, or your best friend's daughter? Do these girls hear you talk about menstruation as something you dread, hate, or can do without? Do they experience the wrath of your mood swings, irritability, or depression when you are menstruating, because you don't take time for yourself? What message do you think this conveys to them? And if you could convey another message, wouldn't you? Yes, you may say, but I can't convey another message since I'm suffering from PMS symptoms... Here is where I'd like to rock your boat a little (or a lot) by saying: PMS is Not a Requirement! PMS is your (wise!) body's strategy for getting your attention! It is your body's way of telling you that you need to slow down, go inward, release any toxins from the month you've lived, and regenerate yourself for the month ahead. Taking medication for PMS is like taking pills to suppress yawning when you are tired, while all you need to do is go to sleep. When you start questioning the beliefs you internalized about menstruation, when you start caring for your body and allowing it to naturally renew (rather than suppressing its need to rest) you are going to be able to gradually reclaim your cycle as a source of renewal in your life. Not only would you reverse your symptoms, but you could stop the legacy, which our culture has been blindly passing down from one generation to another. Furthermore, you'd be able to model an empowered womanhood to the next generation, starting with your own daughter. She and her peers will, in turn, be able to pass it on to those yet to be born. PMS can stop with you! And together, we can change the world... Thanks to DeAnna L’am for this thought-provoking post. I was navigating the supermarket yesterday, toddler in tow, chatting about all the products we were passing. A constant commentary of the products, decisions about what milk to buy, what colour the bananas are. Inane chatter to an outsider, but I love these outings with my son as he learns all about the world. We read the signs and I wonder aloud whether we need venture down that aisle. We see the ‘fish’ sign, we see the ‘beverages’ sign. We talk about the ‘baking goods’ sign and how we like to bake muffins at home. Then we come to the ‘feminine hygiene’ sign. I had passed such signs countless times before, but with a toddler soaking up all there is to learn, suddenly language has a whole new meaning and importance to me. My chatter is halted for a second - “feminine hygiene”? – and I am not sure how to explain these words.

To give my son a literal explanation, it seems that females must need products to sanitise themselves. Through a young child’s eyes, I look at the marketing – ahh, feminine hygiene products – these must make women don white leotards and dance, put on a skimpy bikini and run through waves, throw on high heels, skinny jeans and grab a microphone. And some have wings! Maybe women can fly after all! As I took a moment to ponder this, my son pointed at the ‘sanitary products’ and yelled out in delight “Mummy’s nappies!” I laughed and agreed - “Those are for women to use when they have their periods”. I could almost feel the man beside us scampering past all these ‘sanitary products’ reel in horror. I was recently alerted to a new advertising campaign by US tampon brand ’Kotex’. According to Mr. Meurer, of Kotex - “We’re changing our brand equity to stand for truth and transparency and progressive vaginal care.” Wow, ‘progressive vaginal care’ – the mind boggles! But thumbs up to them for attempting to ‘get real' in their advertising for their products, by mocking the traditional way that menstruation products are advertised. The advertisement opens with a woman declaring she loves her period, followed by “Sometimes I just want to run on a beach... Usually, by the third day, I really just want to dance... The ads on TV are really helpful because they use that blue liquid, and I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s what’s supposed to happen.’ ” The dialogue is illustrated by clips that had been used in previous Kotex advertisements, furthering the irony of the whole thing. But thumbs down to US television networks who, after viewing the original advertisement, barred the use of the word 'vagina'. Even a revised version, which referred to “down there” was deemed too explicit. To quote blogger Amanda Hess, "Now, the commercial contains no direct references to female genitalia—you know, the place where the fucking tampon goes." The way society frames language shapes the way we feel about things, talk about things. The language we use imposes a particular view of the world. The view promoted by the language of ‘feminine sanitary products’ is that women are dirty and need to buy things to sanitise themselves. Are women’s bodies and their natural cycles really that scary? I am not advocating graphic photography here, but can we not at least acknowledge what the tampons are for? Is the word ‘vagina’ really that offensive? I hope Kodex’s new approach to tampon advertising marks the beginning of a change in the language we use around menstruation. I can't help but think of all the out-there products advertising 'penile erectile dysfunction'. I think again of the world through my child’s eyes. If his sexuality education was left to the media, he’d grow up assuming that women need to buy ‘feminine hygiene products’ in order to wear tight white spandex and dance, or play beach volleyball in skimpy bikinis. He’d also think the ‘products’ were to clean up that funny blue stuff. But for now I am my son’s teacher, and I can filter most of this stuff for him. I dance most days, regardless of what day in my cycle it is, and I most certainly never wear white spandex. |

AuthorRachel is a writer and educator whose fields of interest include sexuality education, gender, feminism and youth development. Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed